"All of them want to come here!"

Is 'the boat full' in the Global North?

To the question

Recently, in the metro in Barcelona, I overheard a conversation between an older man and a middle aged woman. His is the phrase in the title, repeated several times. “They would all come here, if they could. And the South Americans are worse than the Moors...” he continued. The woman answered: “Well I do understand it, they come for the money, I would also go to Switzerland for the money, they earn better than here...”.

Probably if we had looked around we would have seen somewhere a Latin American woman accompanying some elderly person: the visible end in the North of the global care chain (’Latin American women are so soft and caring’... --Nobody said prejudice has to be coherent).

Well, I, as a South American, was fuming silently. But then, just before going out of the metro, I did chime in: “You better look at why people are coming here, look at the companies, many from the North, going there and destroying livelihoods, destroying our world. For example, all the companies buying up land in Argentina... And one more thing [I turned to the woman]: I did not come here for the money” (... well, just to break a stereotype). I stepped out, trembling.

To bring this into context: These kinds of conversations are not common in my dear adopted city, notably allergic to fascism. And, not a minor detail, the above conversation was in Spanish, not in Catalan.

In Catalonia, a racist nationalism is sprouting up, only recently, with the “darkest and most dehumanizing countenance of the extreme right”, in the words of the presenter of “El Matí” a Catalan radio program. He means Silvia Orriols, now the mayor of Ripoll, a small city, who we then hear: “In Catalonia we don’t have a place for everyone and we have surpassed the limit, by quite a bit, ... Those are not poor people, they are barbaric”1 (this last word is pronounced with a menacing tone- one can almost hear the barbarians approaching).

This is hate speech in its purest state. Which, we know, leads to violence. And, here explicitly, we find the idea of a limit.

It can be more than 20 years ago, when I lived in Vienna, when I first heard the question: how much immigration can a country withstand? It came from a colleague and was meant as a reflection. This question left me wondering, for it implies that one could elucidate some percentage indicating an acceptable quantity of Others (my present self is being sarcastic). And very technocratically, the government could arrange for that percentage to be respected...

Recently, I found in Linkedin a similar question raised by a person from the Global South. He pointed out that immigration “has become one of the most polarizing issues of our times”. Well, yes. But he also asked if there might be “too many” immigrants. And also: is there something like “cultural erosion?”, and can a “sense of self” be lost in the home countries?

These questions are today normalized, and sound plausible: immigration has been made into a ‘problem’, i.e. the problematization has succeeded2. But let us look deeper.

The far right

Going back to my outburst, I could read a quizzical look on the man’s face.

The globalized context does not exist in the far right’s over-simplified narrative, which can even deem superfluous to ask why people are coming. For it is ‘common sense’3: ‘It is because of “our” welfare, “they” want to make use of it’. Period. It is important to note that the background belief is: ‘we alone have created our welfare’. The normalized ‘imperial mode of living’, invisibilizing the global dependency of this welfare, is one more joint in the chain that makes the racist narrative possible.

In the past decades, racist discourses have reached mainstream. As Ruth Wodak has said, we inhabit a “post-shame” era, where normalized far-right parties “produce and reproduce their ideologies and exclusionary agenda in everyday politics, in the (social) media, in campaigning, in posters, slogans and speeches”. The exacerbation of anti-immigrant discourse in Spain is rather recent4, compared to other European countries. Nonetheless, these discourses about the ‘Other’ of Europe do have deeper roots: in coloniality, as inseparable of modernity.

Basically: the main issue is not an actual ‘cultural erosion’. It is important to note that the places with most immigration are not the places where the far right discourse is effective. For example, the triumph of the far right AFD in the elections in Germany in 2025 happened in the East, where there is less immigrant density. The main issue is created fear.

The political returns of stirring fear, of hate speech, seem to be worth it, even if with racist politics you shoot yourself in the foot.

A flawed question

Going back to the scene in the metro, I basically went for an argument which could be summarized as: ‘if you want to solve a ‘problem’, look at the causes, not the symptoms. The goal would be: let us fix global injustices. But there is faulty, imperial logic here, as I am implicitly accepting that ‘they’ are a problem.

There is a related, humanitarian argument, pointing out how immigration is necessary for the present system. It presents a win-win scenario... actually arguing for the reliance on and continuity of global injustices.

So let us take another stand. Global capitalism may be the main driving force behind migration today towards the North, with forced misplacement playing an important role. But there is also agency. ‘We’ are also coming because the Earth is ours to tread, because it is everybody’s right to flee from impossible circumstances or to venture into possibly better futures. It is human to move around, we always have (see D. Graeber). Global Northerners make use of this right (today an imperial privilege), also when only visiting those countries “down there”.

Let us go in another direction and rather question the validity of the problematization itself: one of the main societal problems right now in Europe is excessive migration. It isn’t. But there is also the limits topic, and the metanarrative: there is a maximum of ‘strangeness’ that a nation can assume.

However: Nations are “imagined communities” (B. Anderson). They don’t exist outside our own cultural creation. That doesn’t make their effects less real, but it makes it irrelevant to find out what percentage of same-colored people they should have. Besides, nations-as-a-pure-ethnicity is just one possibility of understanding them. For they can also be based on citizenship and a social contract, for example, following the course that Latin American nations took.

Outlook

The far right is juggling with, unfortunately highly contagious, late-modern phantasms. Distracting societies from confronting the real, huge crises humanity as a whole is facing. All of our best developments and ideas for a life of wellbeing for all don’t have a chance in a world taken over by the extreme right.

Possibly, talking directly to people, intervening in conversations, and perhaps putting forward the real, urgent issues we are facing, is a suitable scheme to counteract fallacious, racist, narratives. But what factors should be considered in order to intervene positively? A complex theme, to be continued...

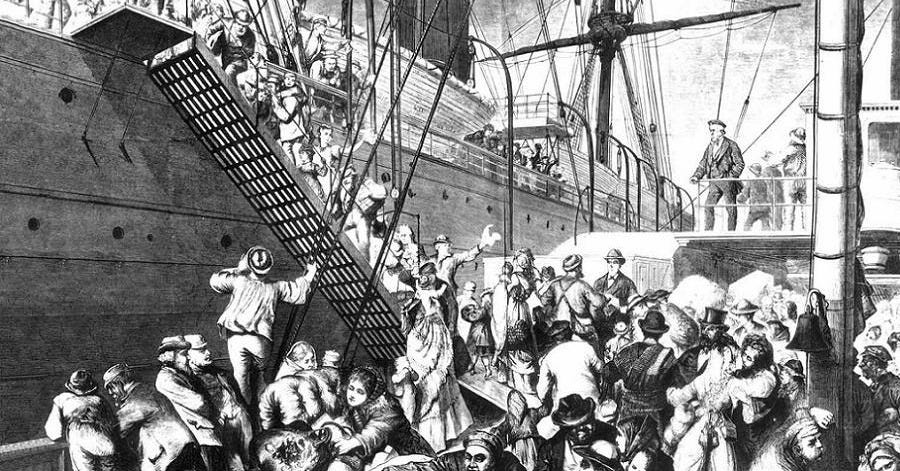

Photo 1: German emigrants boarding a steamer in Hamburg, 1874 (Wikimedia commons).

Photo 2: El Setembre. c.c

In the original catalan: “A Catalunya no hi cap tothom i hem sobrepassat, i de molt, el límit en termes migratoris... Això no són pobres, això son bárbars” (translation by the author).

“They” have been focused as such, while matters such as financial capitalism or speculation (as with living quarters) remain vague and unseen, belonging to the european (civilized) ‘us’, and the, so considered, inevitable order of the economy. To realize how this works, in Spain we can look back at the uprisings of 2008 where the banks were clearly perceived as the responsible entities for the crisis, Vox and racist discourse had not yet emerged forcefully.

For an investigation about Austrian Far Right’s construction of “common sense” see Ruth Wodak (2024).

With the rise of the far right party: Vox. One previous article of mine about this here (in spanish).

This is so powerful!

I love the rebellion against problematisation, the clear articulation of global injustice, and the reminder that we should cherish — and feel grateful for — the chance to live alongside people with whom we might otherwise never have had the opportunity to coexist.

How do we explain this to the broader public?

1. The problem isn’t migrants — it’s an excess of tourists, millionaires, and pointless abundance.

2. Global inequality, imperialism, and unequal exchange are the real drivers of involuntary migration.

3. We should be grateful for the life-changing encounters that global coexistence makes possible, especially when they unfold under conditions of equity and conviviality.

This reminds me of the Lifeboat scenario - the moral exercise that asks participants to decide who should be sacrificed and who chosen to fill limited spaces on the lifeboat from a sinking ship. When I was a participant many years ago it was a harrowing experience. The wrestling with conscience and emotion was excruciating. What none of us thought to question was the premise that the boat was sinking.

In a world of fear-mongering we are caught up in the narrative and feel forced to take a position and the vehemence that often accompanies it is the shield to protect us from the uncertainty and discomfort we really feel.

It difficult not to buy into these narratives when all around you see decline and scarcity and you have already backed up to the proverbial wall either mentally or in actuality. Now it is a game of them or us. We have been given the rules of a game that we have played for so long we can no longer conceive of it being different. That is, perhaps, the real Matrix. In this one though the red pill gives you access to a reality that is abundant, loving and vital.