The end of abundance

Why democratic and ecological rationing must be the future

For decades, our economic system has been built on the idea of infinite growth, unlimited consumption, and constant technological progress. But today, as we face climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion, this system is proving unsustainable. The challenge now is to rethink how we use and distribute resources fairly while respecting ecological limits. One of the boldest proposals in this debate is democratic and ecological rationing, or self-limitation, a new way of organizing the economy and allocating resources that shifts decision-making power from markets and technocrats to communities and democratic processes.

The problem: when price decides who gets what

In our current economic system, resources are primarily distributed through price rationing. That means that access to goods and services depends on how much people can afford. If demand for a scarce resource increases, prices rise, and only those with enough money can buy it. This system favors the wealthy while excluding the poor from basic necessities. In 1977, amid the U.S. energy crisis, economist Martin Weitzman questioned whether price rationing truly meets real needs, arguing it often benefits the wealthy:

“If a market clearing price is used, this may mean only that it will be driven up until those with more money end up with more of the deficit commodity. How can it honestly be said that such a system selects and fulfills real needs when awards are being made as much on the basis of income as anything else?.”

Amartya Sen's work also highlighted this issue, especially in the context of famines. His analysis of the 1943 Bengal famine demonstrated how those who saw an increase in income were able to purchase more food, which drove prices up and further excluded those without income increases from accessing essential supplies. These examples illustrate how price rationing systematically prioritizes wealth over genuine need, reinforcing inequality rather than ensuring fair access to essential resources.

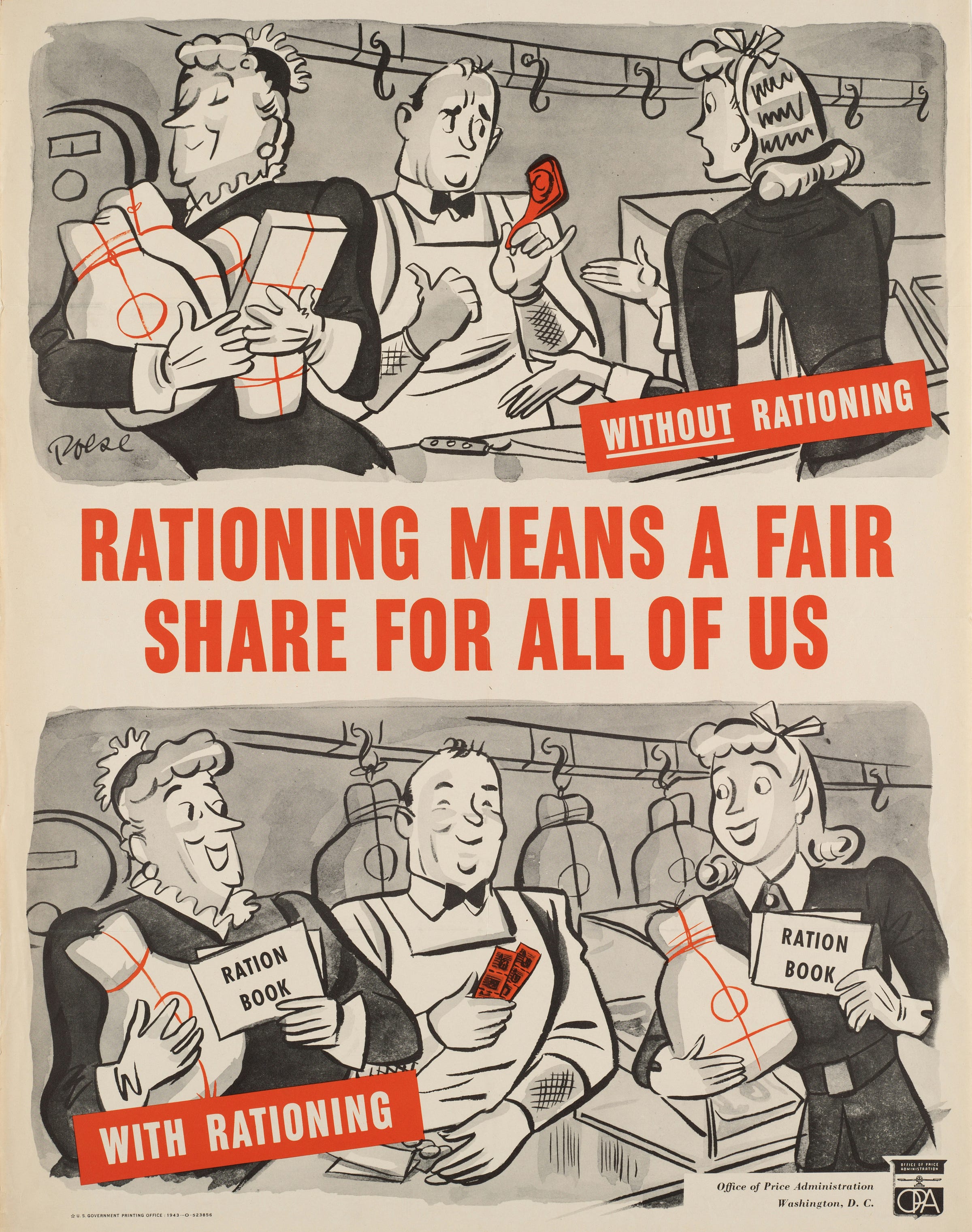

Why rationing?

Unlike price rationing, which distributes resources based on ability to pay and favors the wealthy, quantity rationing provides a more equal and fair system by ensuring that everyone receives an equitable share of essential goods, regardless of income. The major economic innovation behind quantity rationing is that it introduces ration points as a parallel currency to money, allocating goods through coupons instead of market exchange, giving each item both financial and non-financial values. By introducing this parallel currency, rationing creates both a personal and interpersonal zero-sum dynamic. Indeed, individuals must allocate points wisely, while collective consumption remains interconnected—excess by some limits access for others, fostering interdependence and requiring democratic distribution decisions.

Rationing allocates goods based on social utility and resource use, rather than market value, to encourage resource savings and promote equality in purchasing power. Unlike market-based systems, rationing gives everyone the same number of points, reducing income disparities in access. However, it doesn't fully equalize purchasing power, as individuals' ability to purchase goods still depends on their financial capacity beyond the points. For instance, wealthier individuals can more easily afford additional goods, even with the same ration points, unless prices are controlled.

But why could rationing be important today in the face of ecological crises? Rationing could be a key tool to restore balance between the economy and the environment. By adjusting human activities to fit within the planet's natural limits, ecological rationing follows what Passet calls “normative management under environmental constraint.” He proposes a three-step process: first, setting sustainable limits for natural resource use; second, ensuring these limits are fairly shared within society; and third, creating institutions to help people make choices that respect these limits. Designing a rationing system satisfies these criteria as it would involve quantifying ecological limits, distributing them fairly, and promoting social justice, all while being guided by political and economic institutions. In essence, rationing institutionalizes ecological limits, fostering robust environmental integrity.

Rationing is effective because, when applied to all resources, it prevents rebound effects, where efficiency gains lead to increased consumption, either directly (e.g., fuel-efficient cars being driven more) or indirectly (e.g., savings from efficiency spent on other polluting activities). Such effects undermine efforts for sustainable consumption. In partial rationing models, people often spend savings on non-rationed goods, increasing demand and prices, creating a "whack-a-mole" effect. However, in rationing systems applied to all goods and services, the total consumption of resources is controlled, preventing the rebound effects that arise when savings from efficiency improvements are spent on increasing consumption of non-rationed goods.

From imposed limits to collective self-limitation

Rationing has been used throughout history, especially in times of war and crisis. In the UK during World War II, rationing helped ensure that food and fuel were fairly distributed, preventing shortages and social unrest. It was widely accepted during wartime because it was seen as a just system—one that applied to rich and poor alike. However, in wartime UK, the rationing system was imposed due to exceptional circumstances and not as a deliberate form of self-restraint, which was revealed to be an existential weakness. When rationing continued beyond the war, justified by export demands, supply shortages, and the need for fair distribution to avoid price hikes, it was no longer seen as a wartime necessity but as a prolonged austerity campaign, with the home front seemingly operating without the support of war.

This ongoing austerity fueled public discontent, further amplified by mass communication efforts led by powerful economic interests, such as clothing manufacturers, who campaigned against rationing. In contrast, the Labour Party’s socialist faction saw rationing as a way to preserve consumer autonomy. These pressures contributed to the Conservative Party’s victory in 1950, which promised to end rationing as soon as it was elected. Without strong public support or structural change, rationing remains vulnerable to economic pressures.

A democratic and ecological alternative to rationing could be proposed: self-limitation. Unlike rationing, which is imposed by technocrats through arbitrary rules, self-limitation is a democratic initiative that empowers citizens, shifting decision-making away from experts. The key difference between rationing and self-limitation lies in how the rules governing resource, goods, and services distribution are created and enforced. Traditional rationing, whether quantity-based or price-based, often involves top-down control (e.g., by unelected officials or impersonal market forces). In contrast, self-limitation is shaped democratically by communities, ensuring that rules are not only accepted but actively desired. Achieving this requires democratic processes where collective deliberation fosters participation in creating and enforcing rules.

Democratic deliberation in a self-limitation policy aims to regain control over our needs, which the capitalist system shapes by altering how we satisfy them and creating artificial demands, ultimately by reclaiming control over production and consumption. It aims to limit resource consumption, distribute equitably, and empower communities to shape and restructure society’s material base — the infrastructure, technologies, and economic structures that determine how resources are extracted, transformed, and distributed. Through deliberation, individuals collectively decide which social needs to prioritize, the energy and materials required to meet them, and the environmental limits to respect. This process transforms how society allocates its financial surplus and investments, replacing profit-driven logic hijacked by capitalist firms with one that focuses on ecologically sustainable needs, with profits pooled and directed according to social priorities.

Photo credit: Boston Public Library

Kudos, I would change the title, as rationing is the end of scarcity for at least two billion people.