"Is AI more important than climate?"

What Google CEO's Answer Revealed About Energy Optimism and Planetary Reality

When the BBC recently asked Google and Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai whether the build-out of AI is more important than climate, the question briefly cut through the hype that usually surrounds the AI boom. Pichai acknowledged that AI is dramatically increasing energy in ways current systems “can’t fully cope.”

But rather than questioning whether this acceleration is compatible with planetary limits, Google’s response to rising energy demand is simply to scale supply. Pichai spoke of “extraordinary investments” in solar, battery technology and nuclear.

In other words: when AI strains the system, the answer is to build a bigger system, not reduce the strain. As a self-defined technologist, he expressed confidence that “we will have abundant renewable energy in the future.”

As a former Googler who now advocates for post-growth business transformation, I recognised that worldview intimately. I had internalised it early in my tech career: growth isn’t something to question - it’s something to optimise.

Scale is always the solution, never the problem.

And Pichai made that worldview explicit when he warned governments, including the UK, that they “don’t want to constrain an economy based on energy,” because such limits “will have consequences.” In other words: economic growth must not be stalled, therefore energy supply must expand indefinitely to support it. This is precisely where technological optimism diverges from ecological reality.

Tech worries about financial overshoot. The real crisis Is planetary

When Pichai said “there are moments we overshoot collectively as an industry,” he was speaking about financial bubbles: the dot-com era, crypto, VR.

Economist experts like Grace Blakeley warn the AI boom may be another bubble fuelled by hype and geopolitics, noting that when it bursts, it’s those who profited most will be shielded, while the public bears the cost.

But even if the AI bubble pops, there is a far greater overshoot already underway: the overshoot of Earth’s life-support systems.

Right now, it is Earth’s life-support systems, upon which all markets depend, that are breaching their safe limits.

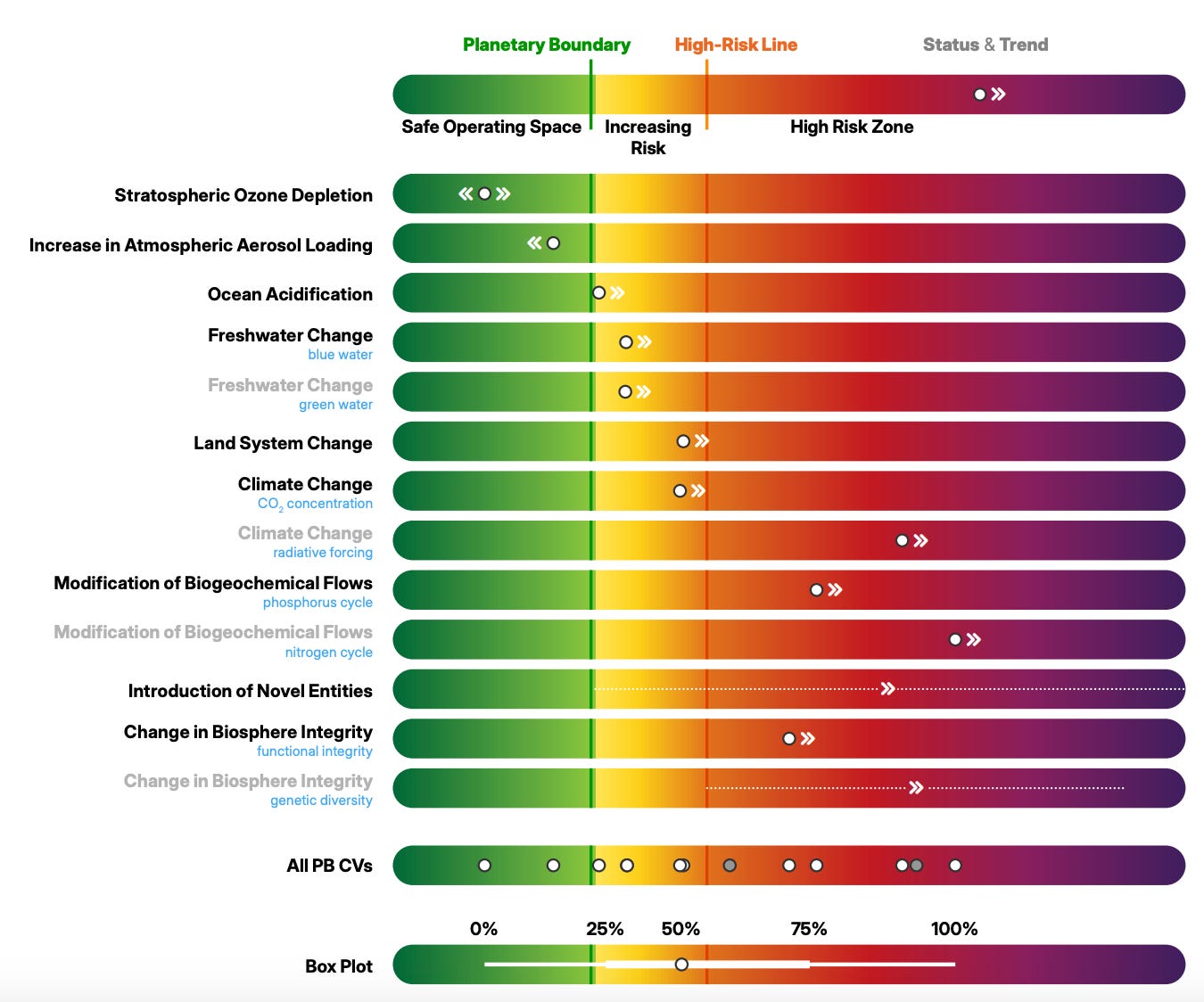

According to the 2025 Planetary Health Check report, humanity has already breached seven of the nine planetary boundaries, including climate, biodiversity, freshwater stability, land use and chemical pollution. These boundaries are not abstractions; they are the ecological foundations on which stable societies depend.

A market bubble can be bailed out. A biosphere cannot.

Tech leaders fear the return of speculative bubbles. But the bubble that truly matters, the biophysical one, has already burst:

The largest private build-out in history

Google alone plans to invest $90 billion annually on AI-related infrastructure, as Sundar confirmed in the BBC interview. Across the industry, AI-related capital spending now exceeds $3 trillion.

This is the largest private capital deployment in history, emerging in the exact decade scientists insist we must reduce global energy and material throughput to stay within ecological limits.

We are scaling the most energy-hungry computational paradigm humanity has ever built, precisely when the world can least support it.

AI isn’t digital. It’s physical.

Data centres account for under 3% of global electricity use, yet this year it’s projected to rival that of Japan. By 2030, they could consume 1.2 trillion litres of water annually — enough for four million U.S. households — even as around a quarter of today’s data centres sit in regions facing water scarcity by 2050. According to Google’s own 2025 Sustainability Report, the company’s total water consumption rose 28% by nearly 1.8 billion gallons from 2023 to 2024.

The AI industry rests on a bold assumption: that renewable energy will scale fast enough to absorb its exploding demand. But renewables are neither frictionless nor infinite.

Solar panels and wind turbines last 20-30 years and depend on mining of finite materials, often in regions already facing water scarcity and political exploitation. Nate Hagens expresses the core misconception clearly when he renames renewables as “rebuildables” and reminds us that maple trees and chickens are renewable, but technologies like EVs and solar are not!

This constraint is already visible. The IEA warns of looming shortages in key minerals, including lithium, the so-called white gold of AI infrastructure, as early as the 2030s. In other words, the energy transition required to sustain exponential AI growth is itself bounded by finite materials.

Net-zero solves for carbon, not the conditions for life

Net-zero has become the dominant climate strategy of the tech sector, but it largely functions as an accounting ledger rather than a plan for reducing harm.

It allows companies to continue emitting now, relying on future carbon removals and shift ecological burdens disproportionately to the Global South. Google did stop counting emissions-avoidance offsets towards its net-zero goals in 2023, pivoting instead to carbon-removal credits.

But even removals don’t address the broader issue: carbon is only one dimension of ecological stability that scaling AI impacts.

The problem? Carbon credits more broadly don’t undo harm; they replicate it. Earlier this year on my podcast, Responsible Design expert Cecilia Scolaro explained it like this:

“if you do not go deep enough in understanding the harm that you’ve been doing, whatever sustainable solution you’re going to come up with is going to replicate exactly the same mechanism.”

Net-zero is a carbon accounting strategy, not a plan for planetary stability. This thinking is however being built directly into the energy infrastructure proposed to support AI. In its 2025 policy paper, Powering a New Era of American Innovation, Google argues that scaling AI will require continued investment in fossil energy, (reframed as natural gas paired with carbon capture and storage (CCS)). This is presented as pragmatism: the only way to meet exploding data-centre demand without slowing innovation.

But as physicist-economist Erald Kolasi put it it in our recent conversation, CCS was developed by the oil industry for enhanced oil recovery and “ignores upstream emissions, downstream emissions, and the energy required just to keep the system running.”

If that’s true, CCS isn’t a bridge to sustainability: it’s net-zero logic made physical: the emissions are piped away, extraction continues, and the growth imperative remains untouched.

So, is AI more important than climate?

It’s the wrong question. The real question, left unanswered in the interview, is this:

What scale of AI is compatible with a finite, destabilising planet?

Scaling energy- and material-intensive technologies while breaching multiple planetary boundaries is not innovation. It’s blind hope, disguised as progress.

The coming decade will not be defined by AI versus climate. It will be defined by whether technological ambition can be brought back within the biophysical limits that sustain life. And crucially, this shift is not only being demanded by scientists or activists.

Professionals want a different type of business

While investors and executives push for unconstrained acceleration, my research with the LSE Post-Growth Transformation Lab found that the majority of UK professionals working in for-profit organisations believe businesses should operate within social foundations and ecological boundaries, in line with doughnut economics principles. In other words, the people building and running these systems already understand what leadership had yet to admit: limits are not anti-innovation — they are a condition for long-term business legitimacy and survival.

Scientists have been calling for transformation for decades. Now, our biosphere is enforcing the lesson if we’re ready to act on it.

Photo 1: Matthew Henry in Unsplash / Photo 2: Planetary Health Check