Degrowing tomorrow in today's soil

Why regenerative agriculture and forestry can be essential for a liveable future after capitalism

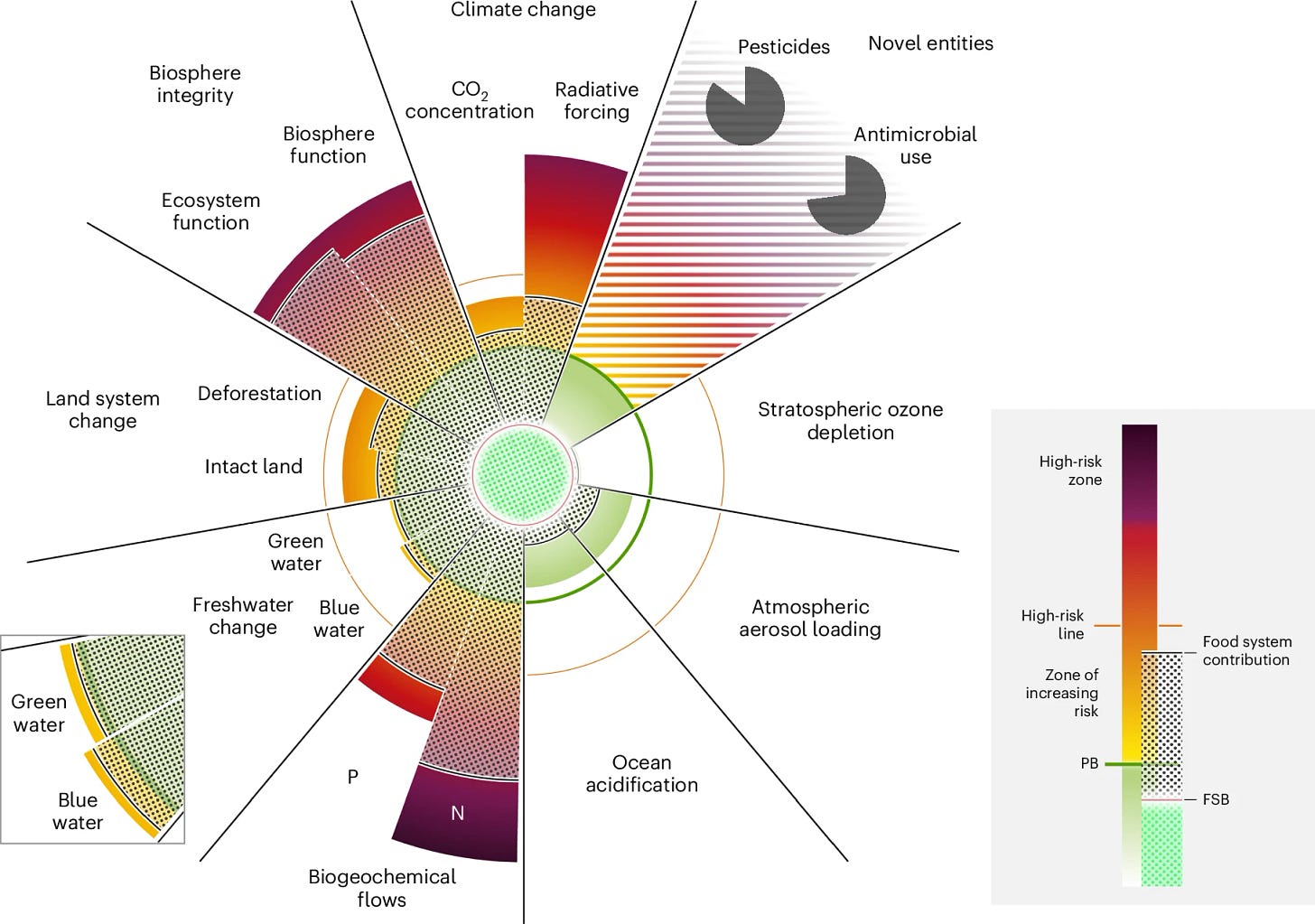

2026 has begun with yet another sign of an exhausted imperial system that can no longer maintain its hegemony through propaganda alone. Increasingly, it relies on force to secure access to fossil fuels and other key resources, doing so at the expense of our collective future and the sovereignty of nations. We’ve entered a period in which nearly all planetary boundaries have been transgressed, the working class suffers from universal artificial scarcity, and billionaires openly engage with fascism.

In this context, it is difficult to identify sources of hope: strategies that are realistic, yet genuinely transformative and capable of protecting societies from socio-environmental collapse. This post explores how our world can thrive even as capitalism collapses.

My main claim is that regeneration work, together with resistance organising around ecosocialism (via unions, parties, media, communities), offers the most promising avenue towards desirable futures where no one is left behind. I will explain the opportunities and challenges of regenerative agriculture systems in this post as an introduction, and throughout the year in more detail.

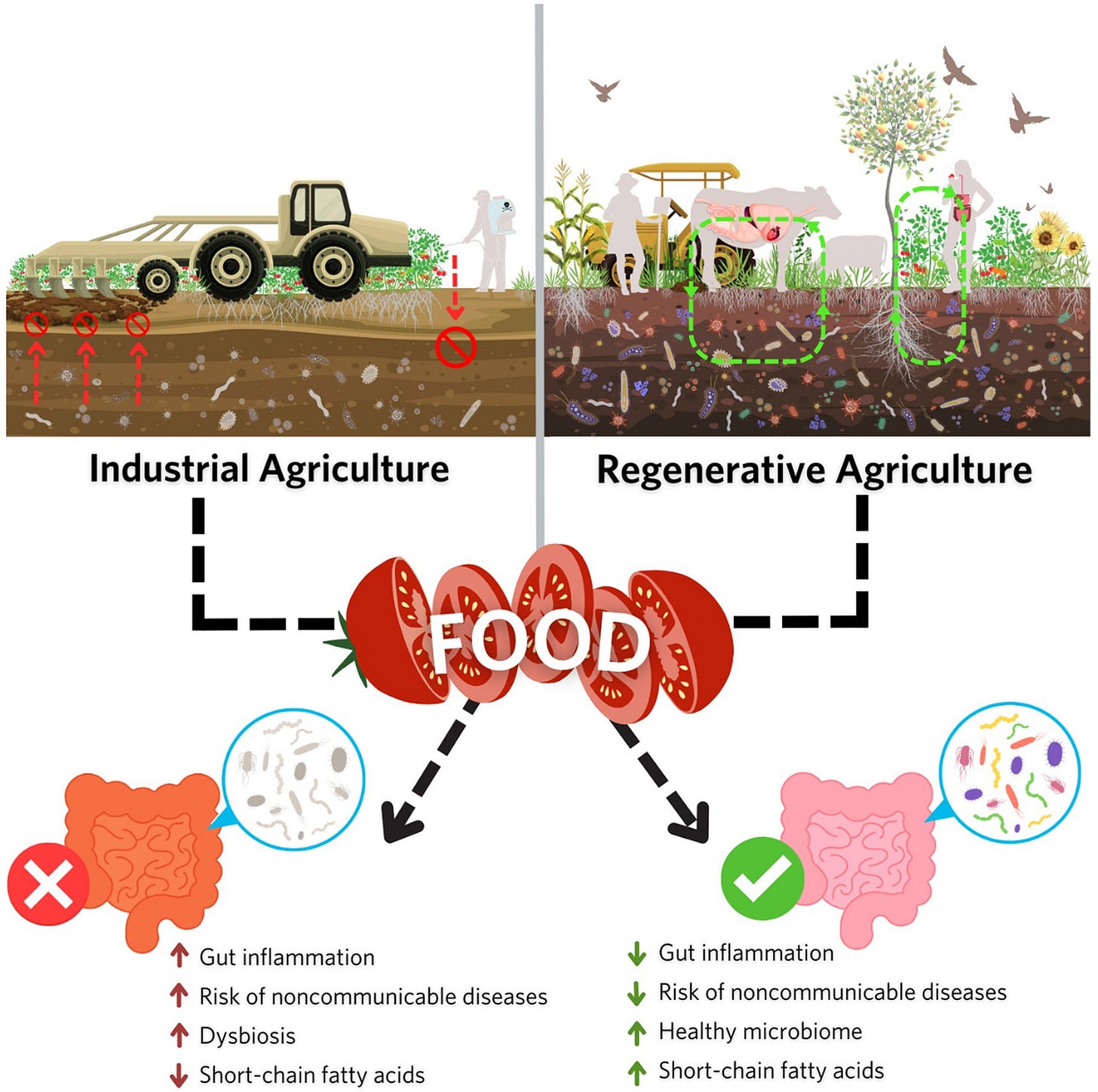

The goal of regenerative agriculture is to bring life, resilience, and prosperity back to landscapes, communities, and ultimately entire ecosystems. It starts from a simple but profound understanding: soil health is the foundation of life and secures our capacity to heal both ecosystems and human bodies. Soil is not only a medium that provides nutrients to plants, microbes, and ultimately people; when healthy, it also acts as a sponge that retains water, cools the land, absorbs carbon, and buffers extreme weather events such as floods and droughts.

The principles of regenerative agriculture are relatively clear. Maintaining diverse plant cover, minimising tillage, and removing manmade chemical inputs do not merely avoid damage—they actively improve the soil’s capacity to deliver essential ecosystem services at scale, even under increasingly extreme climatic conditions. This approach goes far beyond creating beautiful landscapes full of bees, butterflies, and greenery.

Soil health is entirely connected to our own, as only healthy soils enable our food to provide essential micronutrients and bacteria to our gut. Recent research shows that gut health is closely connected not only to physical functions but also to mood and overall wellbeing. Industrial agriculture harms the soil via pesticides, excessive external fertilisation and tillage, limiting the capacity of our foods to provide nutrition instead of poison.

When designed properly for specific climates, crops, and cultures, regenerative agriculture can scale to feed a global population while remaining productive and economically viable. It has the potential to provide dignified livelihoods for farmers and to revitalize rural regions suffering from abandonment, isolation, and loss of self-esteem (see La Junquera, RegeneraCat, and LindenGut, among others).

Regenerative farming and forestry may be one of the most important kinds of work of the next 25 years—a pathway away from extractive, fossil-fuel-dependent systems and toward a future that is healthier, more just, and, importantly, delicious. At a time marked by uncertainty and discouragement, it offers an emancipatory and hopeful vision to reconnect with the land, local cultures and futures beyond the urban.

If regenerative agriculture is such a compelling solution, why is it not happening at scale?

Why do we continue to see accelerating desertification and monocultures? The answer is complex, but also painfully simple: Industrial fertilisers and pesticides deliver short-term yield gains at the expense of long-term soil fertility, ecosystem health, and human well-being. They have locked many farmers into cycles of debt, declining soil productivity, and growing vulnerability to climate extremes—while powerful supply chains and supermarket structures continue to squeeze farm incomes. This system produces scarcity, loneliness, and overwork in a profession that should be celebrated as heroic, given its essential role in sustaining life.

Luckily, a significant but endangered part of the land is resisting this cycle of artificial decay. Around 10% of global agricultural land is managed organically—a model that does not always fully overlap with regenerative practices (as soil health could still have some compromises in organic farming like tillage or excessive nutrients), but represents an important step in the right direction. The critical question now is how to support the farmers who manage the remaining 90% of agricultural land in transitioning more easily, restoring local economies, and securing decent livelihoods.

The first step is to understand the root causes of the current soil crisis and fragile food system, and approach solutions with humility. Regenerative agriculture is not inherently vegan, anti-technology, small-scale, large-scale, communal, or private. It can take many forms, and these should be designed by the communities who live on and care for the land. For those of us who are not farmers, our primary role is to listen—deeply and patiently—and then to support their survival first and their transformation later.

Those are questions we need to answer as a starting point:

What are the main struggles and desires farmers have for their landscapes?

What support would they like to have, if any?

How can we support the creation of strong, caring networks where rest is possible?

How can we rebuild community and material security?

How can we include the rural in our collective imaginary as a place of prosperity?

Many of us may choose to reconnect directly with rural areas—not to create isolated utopias, but to work shoulder to shoulder, cultivating abundance in soils, rivers, forests, oceans, and on our tables free from extractivism and unequal trade.

Taking direct part in this tasty revolution—one that carefully selects technologies and practices that genuinely emancipate farmers, reduce dangerous or exhausting labor, and make farming an attractive and viable profession again.

As a future landscape co-designer and transition maker, I propose starting with a simple commitment: engaging with ecosystem restoration at least once a week, whether in rural areas or cities. This can begin by acting as prosumers—supporting regenerative producers, fair working conditions, local markets, and community-supported agriculture—while ensuring that our collective surplus is reinvested in soil and food regeneration. Our research, activism, and work can reconnect with the material reality of land and the stories rooted in it.

Practice must inform theory; we cannot afford to keep filling our bookshelves with utopias while our soils degrade and our rural world sits empty, lacking the cultures of life.

If you love city life, that is perfectly valid. There is still much you can do to support ecosystems regeneration—such as ensuring that the custodians of our landscapes can thrive as well as our environment. This will likely happen if access to culture, music, healthcare, education, energy, housing and mobility is also affordable and safe for everyone in rural spaces, and this can be secured by urbanites through supportive, essential work. This can be done providing them with medical services (remote or village to village), organising music and culture festivals in their villages, or bringing to them the technologies and research that can improve their autonomy and quality of life.

May 2026 be a year of regeneration.

May exhausted systems fade, and living systems thrive, leaving no one behind.

I just shared a story from a 7th generation farm - would love for you to read it!

I am in total agreement with you. I would love to support local farmers and I suspect that there many parts where farmers are part of the community already and welcome support and encouragement. I have lived in several different rural areas in the UK and unfortunately farmers I have come across, small and medium, are quite possessive of their land and production methods.

They would much rather not have rights of way over their land and mechanisation means unskilled labour isn’t required. At the same time they suffer in all the ways you outline and it seems probable that years of trying to work the CAP imposed by the EU and now enduring poorly thought out new agricultural policy from British governments has soured their natural love of the land to the point of deafness over entreaties to consider regenerative methods.

There are one or two regenerative farmers in our region but the majority appear to fall in the above category. There are, too, a few small producers usually cultivating 1 - 4 acres using regenerative practices and I belong to a small nonprofit setting up on some community land to promote sustainable growing and run social and therapeutic horticulture programs.

It feels like too little, too late but my hope is that worsening conditions for our current extractive society will propel people towards the obvious: that being able to feed ourselves is an activity we should all be concerned with and food security looks much more like community growing than large supermarkets.

We can dream!