A Christmas carol revisited, or forming broad alliances

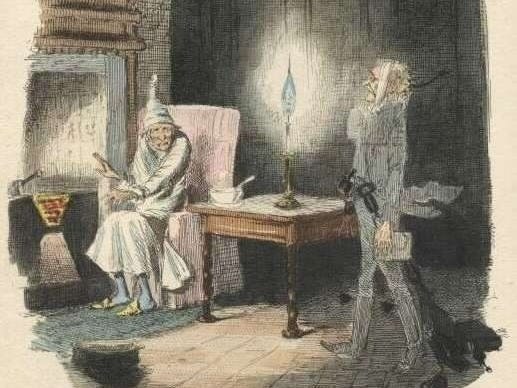

Once upon a Christmas Eve, Ebenezer Scrooge was visited by the ghost of his partner, Jacob Marley, wearing “the chain he forged in life” by his callousness and greed. As Marley discusses his damnation, Scrooge protests,

“But you were always a good man of business, Jacob...”

“Business!” cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again. “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

Marley’s words are often with me, not just during the holidays but all year. I long to repeat them to the billionaire class, the financiers, the proponents of the entire neoliberal project that is plunging our global society into violence and immiseration and our biosphere into collapse (see, for example, Sultana, 2025; Jiang, et al., 2025; Trust, et al., 2025). I long to point out they are wearing “a ponderous chain.” Yet if Dickens were alive today, I expect he and I would disagree about a wide variety of social issues. I am a degrowther and, generally, an eco-socialist; Dickens was a self-described Liberal. I believe in an economic safety net for all people regardless of their merits; Dickens promoted financial assistance for those who deserved it (Orford, 2023, p. 130). I am unambiguously pro-union; Dickens was more conflicted. Nevertheless, if Dickens were alive today, I would want him as an ally. For while I disagree with aspects of his politics, he was a lover of humanity, and we live in a time of unprecedented crisis when all lovers of humanity must unite.

I mean “ally” in the general sense: a person with whom one can work in common cause. Despite notable differences, Dickens shared some core values with leftwing movements such as degrowth, most notably the need to combat poverty. He himself grew up poor, and he was acutely aware of the responsibility of the wealthy to the poor. In A Christmas Carol, he embodies his stance in the allegory of two starving children. The Ghost of Christmas Present tells Scrooge, “This boy is Ignorance. This girl is Want. Beware them both… but most of all beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom...” (Stave 3). He was right.

Now as then, it is ignorance that dooms us, ignorance that drives the practices of waste, destruction, and cruelty that the world’s wealthy inflict on the poor. Matt Orsagh observes that in the US “all programs that support children added together is about ⅔ of what we spend on Christmas [gifts].” Ironically, in the English-speaking world, A Christmas Carol was instrumental in establishing the traditions of both giving family gifts and helping the poor at Christmas. DCPA Press writes that, by the 1840’s, following the pattern of the reformed Scrooge’s holiday giving,

Christmas giving was beginning to be divided into two different activities: gifts for family and friends became “presents” while gifts given to the needy were “charity.” The presents were usually luxury items of a frivolous nature given in person, while gifts to the unknown poor were necessities purchased and distributed by third parties—charitable organizations. Without recognizing it, perhaps Dickens helped establish our gift-giving priorities.

But I don’t hold Dickens (entirely) to blame for this prioritization of frivolities. Our human brains evolved in relatively small tribal groups and are adapted to prioritize bonds with those we know well while fearing strangers. Thus, we are likely to support our family, fear the houseless person on the corner, and have little emotional concept of the famine victim thousands of miles away, even if our own country’s policies created the conditions for the famine. By extension, we may keep Christmas by Black Friday shopping for the family, donating a bag of food to the food bank, and bunging a few dollars in the direction of at least one of the global crises worsened by Black Friday shopping. Our emotional ignorance of those outside our circle perpetuates and exacerbates their want.

I do partly blame Dickens for this. Dickens argued that charity should start at home. With savage wit, he pillories the character of Mrs. Jellyby in Bleak House, a woman who neglects her own children while focusing her energy on attempts to help Africa. This orientation Dickens derides as “telescopic philanthropy” (chapter 4), peering at a tiny and poorly discerned image of a far-off place while ignoring the plight of those beside us. Mrs. Jellyby’s vision for Africa is, indeed, poorly discerned. She hopes, “by this time next year to have from a hundred and fifty to two hundred healthy families cultivating coffee…” (chapter 4). This imperialist project will not help Africa; instead, it is part of a history of oppression and exploitation still ongoing in the coffee industry. Dickens was correct that we generally make clearer, more helpful decisions when focusing on our human relationships. But he provides no answer for our entanglements in systems. The Global North doesn’t do “telescopic philanthropy” well, yet it has devastated the lives of billions of who live “telescopically” far away, so what, Mr. Dickens, do you propose we do? (A plausible answer is support initiatives from the Global South.) Dickens’s reluctance to confront gross systemic injustice is my fundamental quarrel with him–and with the Margaret Thatchers of the world whose only solution is “to help look after our neighbour.” Dickens’s discourse on charity is eloquent as far as it goes; it just doesn’t go very far.

And yet I would want Dickens as an ally–because he was right about ignorance and want, because he used his formidable voice to speak against poverty all his adult life. I do not advocate indiscriminate alliances. I do not call for alliance with eco-fascists or supporters of genocide. But there are a lot of people I disagree with whom I would gladly have as allies. I disagree with Pope Leo about abortion rights, yet I’m glad to be in alliance in support of immigrants’ rights and climate action. I disagree with conservative commentator David Brooks’s idealization of capitalism, but I will happily join the cross-party alliance he advocates in the US to resist Trumpian fascism. A conservative friend once said to me, “We should be able to make common cause about the things we agree about and talk honestly about where we disagree.” This troubled holiday season, I could not agree more.

Photo credit: Scrooge and Marley by John Leech, public domain